Chapter Outline

Chapter 9: Django ORM and Advanced Queries

In this chapter, you will learn:

- How Django’s ORM (Object-Relational Mapper) works.

- How to define models for your Blog app.

- How to use migrations to keep the database schema in sync.

- How to run basic and advanced queries with the ORM.

- How to write tests for models and queries.

By the end, the Blog app will persist posts in a database instead of using an in-memory Python list.

9.1 Django's ORM

We're going to Django’s Object-Relational Mapper (ORM) to interact with a database. Django comes with a sqlite database by default when a project is initiated. But how does Django's ORM work?

Django’s Object-Relational Mapper (ORM) provides a high-level, Pythonic interface for interacting with relational databases without writing raw SQL. Instead of manually crafting queries, you work with model classes and QuerySets, allowing Django to translate your Python method calls into efficient SQL statements behind the scenes. The ORM handles common operations like creating, updating, deleting, and filtering records using simple and expressive syntax—for example, Post.objects.filter(author=user) becomes a SELECT query under the hood. It also manages relationships through ForeignKey, OneToOneField, and ManyToManyField, automatically generating joins and maintaining referential integrity.

By abstracting away vendor-specific SQL differences and providing a consistent API across databases, Django’s ORM speeds up development, enforces best practices, and keeps your data-access logic clean and maintainable while still offering escape hatches when raw SQL is needed.

9.2 Django Models

Django models are the core of Django’s data layer, representing the structure and behavior of the information your application manages. A model is a Python class that subclasses django.db.models.Model, with each attribute mapping to a database column and each instance representing a single row in the corresponding table.

Django models don’t just define fields—they encapsulate business rules, relationships, default values, validation, and custom query logic through the powerful ORM. With models, you interact with the database using clean and expressive Python code instead of writing raw SQL, enabling features like migrations, relationships (ForeignKey, ManyToMany), and robust query abstractions.

Together, models provide a structured, maintainable, and database-agnostic foundation for your application’s data handling, making them one of the most essential components of the Django framework.

9.2.1 Define the Blog Model

Let's define a Blog model that we're going to use to interact with the database.

src/apps/blog/models.py1from django.db import models23class Post(models.Model):4 """Database model for blog posts."""56 title = models.CharField(max_length=100)7 content = models.TextField()8 created_at = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)910 def __str__(self) -> str:11 """Return a human-readable representation."""12 return f"{self.title} ({self.created_at:%Y-%m-%d})"

CharField→ short strings (with max length).TextField→ long text (blog content).DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)→ automatically stores creation timestamp.__str__makes objects readable in Django Admin.

9.3 Django Migrations

Django migrations are the mechanism Django uses to track and apply changes to your database schema over time. Whenever you modify your models—whether by adding a field, changing a data type, renaming a model, or introducing a new relationship—Django can automatically detect these changes and generate a migration file that describes how to transform the database structure to match your updated models. These migration files are version-controlled Python scripts that represent incremental steps in your application’s evolution, allowing Django to understand exactly what needs to be created, modified, or removed when setting up or updating your database. Because migrations are generated from your models rather than handwritten SQL, they help maintain consistency between your Python code and your underlying relational database, regardless of whether you're using SQLite, PostgreSQL, MySQL, or another backend.

Even in a brand-new Django app, migrations are essential because they establish the initial database schema that corresponds to your models and Django’s built-in authentication and session framework. Out of the box, Django ships with several installed apps—such as auth, contenttypes, sessions, and admin—each of which requires its own set of database tables. Running makemigrations (for your project’s own apps) and migrate (to apply all pending migrations) creates these tables and ensures the database is ready to store users, permissions, session data, and other core functionality your application relies on. Even before you write your first model, migrations provide the structural foundation that Django needs to function correctly, and they establish a version-controlled, systematic process for managing future schema changes as you build out the rest of your application.

When you launch Django app using the command we have been using in the last few chapters:

bashpoetry run python manage.py runserver

you should see something similar on the terminal:

bashWatching for file changes with StatReloaderPerforming system checks...System check identified no issues (0 silenced).You have 18 unapplied migration(s). Your project may not work properly until you apply the migrations for app(s): admin, auth, contenttypes, sessions.Run 'python manage.py migrate' to apply them.November ***Django version 5.2.8, using settings 'blogsite.settings'Starting development server at http://127.0.0.1:8000/Quit the server with CONTROL-C.

9.3.1 Create Migration Script

After defining the Blog Model, we need to generate and apply schema changes:

bashpoetry run python manage.py makemigrations blog

This shows the following on the terminal:

bashMigrations for 'blog':src/apps/blog/migrations/0001_initial.py+ Create model Post

This created a brand new migration script, 0001_initial.py in the migrations directory.

Migration files live in an app’s

migrations/directory and are executed in order, allowing Django to build, modify, or roll back your schema in a predictable, controlled way.

9.3.2 Generating a Migration Script

Let's open the newly generated migration script:

src/apps/blog/migrations/0001_initial.py1# Generated by Django 5.2.8 on ***23from django.db import migrations, models456class Migration(migrations.Migration):78 initial = True910 dependencies = []1112 operations = [13 migrations.CreateModel(14 name="Post",15 fields=[16 (17 "id",18 models.BigAutoField(19 auto_created=True,20 primary_key=True,21 serialize=False,22 verbose_name="ID",23 ),24 ),25 ("title", models.CharField(max_length=100)),26 ("content", models.TextField()),27 ("created_at", models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)),28 ],29 ),30 ]

Structurally, a migration file contains a Migration class with two key parts: dependencies and operations. The dependencies list tells Django which migration must run before this one—this ensures changes happen in the proper sequence.

The operations list contains one or more high-level instructions, such as CreateModel, AddField, AlterField, RemoveField, or RunPython. Each operation is written in a database-agnostic format so Django can convert it into the appropriate SQL for your database backend.

When you run python manage.py migrate, Django reads these migration files, determines which ones have not yet been applied (tracked in the django_migrations table), translates the operations into SQL, executes them, and marks them as complete. This system provides a reliable, reversible, and version-controlled mechanism for evolving your database schema alongside your codebase.

9.3.3 Running the Migration Script

Let us now run the generated migration script:

bashpoetry run python manage.py migrate

This shows the following on the terminal:

bashOperations to perform:Apply all migrations: admin, auth, blog, contenttypes, sessionsRunning migrations:Applying contenttypes.0001_initial... OKApplying auth.0001_initial... OKApplying admin.0001_initial... OKApplying admin.0002_logentry_remove_auto_add... OKApplying admin.0003_logentry_add_action_flag_choices... OKApplying contenttypes.0002_remove_content_type_name... OKApplying auth.0002_alter_permission_name_max_length... OKApplying auth.0003_alter_user_email_max_length... OKApplying auth.0004_alter_user_username_opts... OKApplying auth.0005_alter_user_last_login_null... OKApplying auth.0006_require_contenttypes_0002... OKApplying auth.0007_alter_validators_add_error_messages... OKApplying auth.0008_alter_user_username_max_length... OKApplying auth.0009_alter_user_last_name_max_length... OKApplying auth.0010_alter_group_name_max_length... OKApplying auth.0011_update_proxy_permissions... OKApplying auth.0012_alter_user_first_name_max_length... OKApplying blog.0001_initial... OKApplying sessions.0001_initial... OK

9.4 Using the Model

9.4.1 Update the View

Let's update the views so that we may now use the ORM instead of the in-memory list to store posts.

src/apps/blog/views.py1from django.shortcuts import render, redirect2from .forms import PostForm3from .models import Post456def home(request):7 """Render homepage with all blog posts from DB."""8 posts = Post.objects.all().order_by("-created_at") # Get all posts ordered by newest9 return render(request, "blog/home.html", {"posts": posts})101112def create_post(request):13 """Handle GET (show form) and POST (save form to DB)."""14 if request.method == "POST":15 form = PostForm(request.POST)16 if form.is_valid():17 Post.objects.create(**form.cleaned_data)18 return redirect("home")19 else:20 form = PostForm()21 return render(request, "blog/create_post.html", {"form": form})

9.4.2 Update Templates

Update home.html so posts render properly:

src/apps/blog/templates/blog/home.html<!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"><head><meta charset="UTF-8"><title>Django Blog</title></head><body><h1>Welcome to the Blog</h1><ul>{% for post in posts %}<li><strong>{{ post.title }}</strong><br>{{ post.content }}<br><em>Published {{ post.created_at|date:"Y-m-d H:i" }}</em></li>{% empty %}<li>No posts yet!</li>{% endfor %}</ul><a href="{% url 'create_post' %}">Create a New Post</a></body></html>

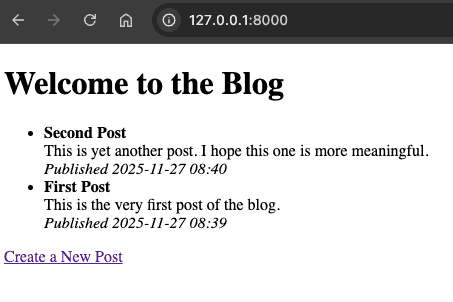

Adding some posts should now display the content on the homepage in the new format:

If you shutdown the server and restart it, you should see the posts saved into the database earlier.

9.5 Testing Models and Queries

We can test the Post model in isolation. The following tests cover creating Post objects, and running some queries against the model.

tests/apps/blog/test_models.py1import pytest2from django.urls import reverse3from apps.blog.models import Post456@pytest.mark.django_db7def test_post_creation_and_query():8 post = Post.objects.create(title="Test Post", content="Hello ORM")9 assert Post.objects.count() == 110 assert "Test Post" in str(post)1112 posts = Post.objects.filter(title__icontains="test")13 assert posts.exists()14 assert posts.first().content == "Hello ORM"151617@pytest.mark.django_db18def test_home_view_displays_posts(client):19 Post.objects.create(title="Visible Post", content="This should appear")20 response = client.get(reverse("home"))21 assert response.status_code == 20022 body = response.content.decode()23 assert "Visible Post" in body

9.6 Chapter Summary

In this chapter we briefly touched some of the concepts behind Django's ORM that is used to interact with a database. We implemented a Post model and replaced the previous in-memory list to save blog posts. This makes the blog posts persist after a shutdown.

In the next chapter we will focus on Django Admin, which is essential for a professional Python Web Development curriculum.

9.7 Further Reading

Check your understanding

Test your knowledge of Django ORM